Several documents from the period suggest that he was. It’s true there are documents that testify to his death and burial at other times and in other locations, but some of these contradict others, and all can be explained as legally or socially necessary if he was, as I believe, to get the privacy he craved by pretending to be dead. Had Oxford lived the kind of life expected of a peer and met normal expectations in most other ways, we should stick to the facts as presented by history. But as those of us know who have read his biographies, Oxford did not live an ordinary life and since so many facts that deal with his writing career are suspect, it’s almost a duty to begin by suspecting them all.

The most suggestive of these documents are:

1) Oxford’s cousin Percival Golding’s statement in a manuscript written sometime between 1609 and 1619 about the Vere family, in which he states flatly that Oxford was buried in Westminster Abbey. Golding is a respectable witness. He’s correct in every other respect, and there’s no reason to think he made this up or was misinformed about the final resting place of his most important relative.

2) Ben Jonson’s statement in his dedicatory ode to Shakespeare in the First Folio (1623): “I will not lodge thee by Chaucer, or Spenser, or bid Beaumont lie / A little further, to make thee a room : Thou art a monument without a tomb.” Jonson was a master of ambiguity, and never more so than in this ode. If these words are pure hyperbole, what purpose do they serve? Why not just say something along the lines of “it doesn’t matter where you’re buried”? Why describe so exactly where he’s not buried? It seems more likely that Jonson was using a rhetorical ruse to impart important information to those readers who wished to pay their respects to England’s great Renaissance poet. Since dedicatory poems in later editions of the Folio would repeat the statement, it’s obvious the point was seen as something important enough that it needed repeating.

3) The complete lack of any mention of his death in letters written to and from his family, friends and associates during the months following his purported death on June 24, 1604, as noted by Chris Paul in 2004 in his article, A Monument Without a Tomb: The Mystery of Oxford’s Death, in The Oxfordian (pages 26-29), one of a number of anomalies he notes connected with Oxford’s passing.

Why, where, and when?

As with so much of his life, mysteries surround Oxford’s death. He either died or retired from public life on Midsummer’s Day, 1604, six months before his daughter’s marriage to the Earl of Montgomery (brother to Shakespeare’s patron, the Earl of Pembroke). Whether he died then or later, it seems clear there was no ceremony, at least, nothing that ever reached the record, nor did he leave a will. In Sonnet 72, Shakespeare wrote, “my name be buried where my body is,” pretty much exactly what we see with Oxford, who appears to have almost totally vanished from the records in the 1590s. This attitude couldn’t be more different from the obsession that most 16th-century peers and their families had with the deaths, funerals, wills, tombs, and monuments of themselves and their exalted forbears.

Despite the lack of evidence, common sense dictates that, if Oxford was Shakespeare, there was a portion of his audience who knew what he’d given the world, that admired him for it, that mourned his passing, and that would have wanted to know where to go to pay their respects. Some part of this audience would certainly have been important enough to make arrangements to have him reburied in Westminster Abbey.

I suggest that it was with Oxford’s burial here and not until then that this spot acquired the name Poet’s Corner.

The history of Poet’s Corner

The first poet to be buried in that spot was Chaucer, or rather, the first to first to have his monument placed there, since his body was buried somewhere else in the Abbey. Chaucer had the spot to himself for 43 years until 1599 when, with a great deal of public fanfare, Edmund Spenser was buried near his monument by the Essex faction, following which a plaque would surely have been set in the floor above his coffin. No longer there, the plaque may have been removed in 1619 when his monument was placed against the south wall (the floor here has been rearranged many times over the centuries) but, following such a well-publicized funeral, there would certainly have been something to show where he lies.

Surrounded by a diversity of memorials, only two of them for poets, one without a body, the other without a monument, seems hardly enough to warrant the name “Poet’s Corner.” One swallow doth not a summer make––or even two.

Following Spenser’s funeral in 1599, it would be 17 years before a third poet was buried in that corner: the playwright Francis Beaumont, in 1616. His plaque is still present (we’re told), though hidden by more recent construction (he never got a monument.) After Beaumont, 20 years would pass until a fourth poet, Michael Drayton, was memorialized, long after the publication of the First Folio and the information in Jonson’s Ode. Drayton did get a monument; like Chaucer, however, he was actually buried elsewhere in the Abbey.

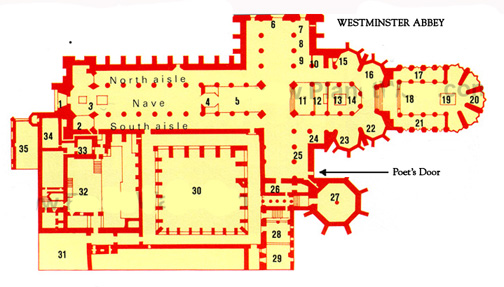

According to Christine Reynolds, the Abbey’s Assistant Keeper in 1999, these three: Chaucer’s monument and the bodies of Spenser and Beaumont, all lie within a few feet of each other in a corner of the nook where “Poet’s door” is located, just beneath the window that’s now being used to honor poets who were never recognized before, most recently Christopher Marlowe.

So when did the corner get its name?

I suggest that it was during the period that Lady Anne Clifford, Countess of Dorset, put up the monument to Spenser that we see today. This took place in 1619, the same year that Oxfordian scholar Robert Brazil gives as the end date for Percival Golding’s manuscript. A leading patron of the arts, Lady Anne had the kind of wealth required to bring attention to English poetry as a national treasure by placing monuments to poets in the nation’s great indoor cemetary. When Michael Drayton died in 1631, it was she who saw to it that a memorial to him was placed in the same area.

Lady Anne was raised to admire the literary arts. A writer herself, author of a famous diary, her tutors in childhood were the poets Samuel Daniel, tutor to the Pembrokes in their youth, and Emilia Bassano Lanier. Lanier’s book, published in 1611, included a long poem in praise of Cookham, the country estate where Lady Anne grew up. Lanier is also thought by many, including myself, to have been the Dark Lady for whom Shakespeare wrote Sonnets 127-152.

Following the death of her first husband, in 1630 Anne would marry Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery. Herbert had a long association with Oxford and Shakespeare’s company. His first wife had been Oxford’s youngest daughter, Susan Vere, and by the time he married Lady Anne he had taken over his brother’s office as Chamberlain of the Royal Household, which put him in charge of Shakespeare’s company.

The likely scenario

For the King’s Men, the period following Oxford’s death (or retirement) becomes increasingly difficult as questions about the authorship continue to be raised along with demands that the plays be published. However, by the end of 1616, Time having brought about certain necessary changes, plans can finally be put into effect. These changes include: 1) William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, has finally acquired the office of Lord Chamberlain and is now in control of all matters connected with the Court Stage; 2) Oxford’s two most powerful enemies are gone: Robert Cecil (Earl of Salisbury) in 1612, and Henry Howard (Earl of Northampton) in 1614; 3) William of Stratford has just died; and 4) Pembroke is now in a position to provide England’s leading playwright, Ben Jonson with a hefty pension, and the honorific title of Poet Laureate. Jonson’s first move is to publish his own works in a collection similar to the one he will be involved in producing for the works of Shakespeare.

The problem for Pembroke, Jonson, and other members of the ad hoc publication committee, is how to resolve the two groups who are at loggerheads over the authorship question. On one hand there’s the Oxford-Cecil family and other high ranking members of Court society (like the Earl of Southampton) who fear the results if connections between the plays and themselves or their family members are made apparent should Oxford’s authorship be revealed. On the other hand, there is a large and influential group who admire Oxford and his works and who want to see him acknowledged in some way. Many in the second group understand the problems of the first group, in fact, some belong to both groups, most notably King James and Oxford’s daughter Susan Vere, Countess of Montgomery.

A plan is created that satisfies both groups. First, Oxford’s plays will be published as a collection in which it’s established for once and all that the author of the plays was his longtime front,William of Stratford, thus hopefully putting a stop to all the gossip and conjecture, or at least, most of it. This will take time, however, for although William has died, his wife, who knows the truth, is still alive; if the book is published she will surely be bombarded by questions, and with her husband no longer around to discourage inquiry, who knows what she might say. Meanwhile there’s much to be done: 1) by editing the plays to make sure that no one still living will be recognized; 2) by acquiring those that lie in other hands than the Company’s; and 3) by purchasing the rights to publish those licensed to various printers.

Second: according to John Hemmings the monument to William’s father in the church in Stratford that the Company helped pay for can probably be altered in some way to look like it was made for his son. Finally: to appease those who wish to see Oxford honored, both as a poet and as the scion of one of England’s most noble families, they can have his body reburied in the Abbey, possibly near Chaucers’s monument where Beaumont was recently buried. This at least can be done right away.

It seems that it would have taken very little for some high-ranking official to have acquired a license from the Dean allowing them to bury Oxford in the Abbey. During the period in question, 1616 to 1619, the Dean would have been either George Mountain (1610-17) or Robert Tounson (1617-20). Neither seems to have been the sort to stand in the way of a funeral arranged by important courtiers, one that brings needed funds into Abbey coffers and that takes place at night and leaves no marker.

Christine Reynolds notes that Abbey funerals were often held at night. Perhaps because it was quiet then so no conflicts would arise with the many religious ceremonies that took place on a regular basis during daylight hours. Funerals of the nobility whose deaths were questionable or lives thought shameful in some way were more liable to be buried at night, (as was Arabella Stuart in 1516, who had gone mad from her long imprisonment in the Tower (Kings 146).]

A funeral scenario

Night: Midsummers Eve: Silently the coaches pull up to the entrance known as Poet’s Door. By torchlight, the coffin, brought to the Abbey by an undecorated hearse, is carried the short distance into the church through Poet’s Door by eight of Oxford’s most enduring admirers and supporters. The floor has been opened in a spot midway between the coffins of Spenser and Beaumont (who do not have to be moved) and the ceremony begins. The musicians who composed for his plays and played for the King’s Men play music he wrote himself or that was written for his plays by composers who were his friends, like William Byrd and John Farmer. The actors speak some of his most moving lines on death and resurrection.

Among the mourners are surely the Herbert brothers, their mother Mary Sidney Pembroke, an assortment of patrons and other lords and ladies who knew Oxford in life, the poets and playwrights who admired and imitated him, the actors and printers who brought his works to life and to the reading public, and of course Ben Jonson, whose monument will someday be placed so he can gaze for all eternity on the spot where his Star of Poets is buried. Tears are shed, poems are tossed into the grave, it’s closed, the paving stones replaced. The company embraces and departs in silence, the candles are snuffed out, the door is closed.

Good night, sweet Prince

We have no way of knowing exactly where Beaumont and Spenser were buried. The floor plaques have been replaced and rearranged many times since those days. Nothing is there to show just where he lies, but those who wish to honor him may still do so, a few steps out from Spenser’s monument, just below Jonson’s bust, in front of Poet’s door, and below the window that now bears Marlowe’s name.

What if we were to gather on the evening of June 23rd every year outside Poet’s Door, and gather beneath the great window, then enter in silence into the space that Ben Jonson tells us was his final resting place, to listen to his words recited by actors and to music by Byrd and Farmer? How great would that be?

I’m going to visit the Abbey week after next. Is there anything I can do to assist in your work here?

Thanks, Gary. Let’s see. If you have a camera, one that’s not too obvious, you might try getting a picture of the spot outlined by Jonson. When I was there I hadn’t yet figured out where it might be, so didn’t get a good shot. Try to get back far enough to show a bit of the window, Poet’s Door, some of the floor, and Jonson’s bust.

Also, if you’re there during business hours you might ask to do some research in the library. Say you’re looking for evidence of night burials, and are particularly interested in burials between the years of 1616 and 1620 for a book you’re writing on night burials in English cathedrals. I doubt you’ll find anything, but it’s great to see the Abbey library. Don’t mention Oxford. Good luck and let us know what transpires.

Also, make sure you see the Cecil tomb. A good shot of Anne Cecil’s effigy is always useful. If I think of anything else I’ll let you know.

John Milton’s poem in the second folio – original type setting – may give you more clues.

Interesting. Is it available online?

http://www.artofeurope.com/milton/milt2.htm

I don’t know how true it is to the original print but the general idea is there

I get your point. Milton’s poem makes no sense with regard to William, who had both a monument and a stone tablet, but they work very well for someone buried without either. Thanks!

Believe it or not the Shakespeare Monument at Stratford Monument tells you exactly where he is buried – and you were right! Please find time to read this essay if you can. It has just been posted and supports your thesis with interesting new evidence:

Click to access AW-2014Oct-Monument.pdf

Very best, Alexander

A few more interesting facts re burial in the Abbey circa 1618-19. Hugh Johnson, vicar of Hackney, died 1618, replaced by Donald Dolben in 1619. During the interim, only a rector would be present at Hackney to allow OXford’s body to beexhumed. William Stanley and Elizabeth de Vere (Earl & Countess of Derby) had a house in Cannon Row (5 minutes walk from the Abbey). Percival Golding was sub-letting rooms in the Strand from 1611 to 1615. Robert Tounson was raised to become Bishop of Salisbury Cathedral (Wilton House area) in 1620. yondThis

So what do you make of this, Jan?

Only that it may give a possible date and some practical details to your scenario. The re-internment could have been very conveniently done between the death of Hugh Johnson (vicar of Hackney) in 1618 and the arrival of David Doulben (the next vicar of Hackney) in 1619, with only the rector of Hackney there to arrange the exhumation. The request must have come from members of Oxford’s family. And these are also the years, I believe, that the First Folio starts to be put together. So it fits into this time-line:

1617 – William Herbert (Lord Chancellor) and Chancellor of Univ. of Oxford and he gathers Oxford-educated poets into his circle, e.g. William Basse, William Browne, Leonard Digges, James Mabbe et al.

1618 -19 – Oxford’s body transferred to Westminster, where the Derby’s have a house in Canon Row; Percival G. has recently been subletting rooms in the Strand 1611-1615 or later

1619 (May) – Wm. Herbert’s directive to the Stationers’ Company not to print King’s Men plays without permission

1619 (July) – Ben Jonson awarded honorary MA from Univ. of Oxford and said to have received ‘pension’ from Herbert.

1619 – Richard Burbage dies; Heminges & Condell retire from the stage (aged 43 and 63 respectively).

1620 – Quartos and manuscripts collected together for editing then printer

Going back to the reinternment in Westminster, notably William Stanley & Elizabeth de Vere had a town house in Cannon Row (remembered in today’s Derby Gate and Derby Street off Cannon Row). So the reinternment feasible (as stated by Percival Golding and seemingly alluded to by William Basse in his ‘Shakespeare’ elegy) and that the instigators were the ‘incomparable pair of brethren’, William Stanley & Elizabeth Vere, Susan Vere, and Percival G. (all family) – with the help of the rector of Hackney and the Dean of Westminster. The Dean of Westminster from 1617 to 1620 was Robert Tounson (d.1621), who in the last year of his life was raised to become Bishop of Salisbury (1620-21) – almost certainly through the influence of William Herbert (as Wilton House is in the ecclesiastical see of Salisbury). Once they’d got the coffin to Cannon Row, it’s only a 5 minute walk to the Abbey.

Thanks, Jan. Most helpful!

I’m just doing my usual thing – ‘joining the dots’ between people, places and times…!

Thanks again!