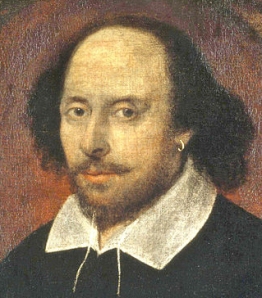

What did Shakespeare look like?

Like so many other questions about the life of our greatest literary artist, the answer is “we don’t know.” And like so many of these answers, that they don’t know what he looked like isn’t just an interesting footnote, it’s a major anomaly. When we have good oil portraits for four of the five poets who accompanied Shakespeare into literary glory, playwrights Ben Jonson and Christopher Marlowe, poets Philip Sidney and Sir Walter Raleigh, why not their master? (That there has never been a reliable portrait of the fifth major poet of the period, Edmund Spenser, is probably for the same reason that there hasn’t been a reliable portrait of Shakespeare.)

Jonson and Fletcher

The Ben Jonson portrait happens to be one of the most outstanding paintings from the period. In an unusually free style that looks towards Rembrandt, it was painted in 1617 by Abraham Van Blyenberch, a Flemish artist who also painted more conventional portraits of the teenaged Charles II and Jonson’s patron, the Earl of Pembroke. Pembroke, Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household by 1617, was one of the “grand possessors” responsible for publishing the First Folio. So why no portrait of Shakespeare, Pembroke’s protégé and Ben Jonson’s “idol.”

The Ben Jonson portrait happens to be one of the most outstanding paintings from the period. In an unusually free style that looks towards Rembrandt, it was painted in 1617 by Abraham Van Blyenberch, a Flemish artist who also painted more conventional portraits of the teenaged Charles II and Jonson’s patron, the Earl of Pembroke. Pembroke, Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household by 1617, was one of the “grand possessors” responsible for publishing the First Folio. So why no portrait of Shakespeare, Pembroke’s protégé and Ben Jonson’s “idol.”

Playwright John Fletcher, who flourished at the Court of James I, rated two top quality oil portraits, this one in the National Portrait Gallery, the other at Montacute House, both painted around 1620 by unknown (continental) artists. Neither Jonson nor Fletcher were aristocrats, which means that the quality of their portraits is attributable to their status as artists, not to their social importance, as is true of the portrait of his co-author, Francis Beaumont, a member of the nobility, which we’re told now hangs at Knole Park (I couldn’t find a good image of it online). We know it best from the engraving George Vertue made from it decades later.

Christopher Marlowe

Although not of the highest quality, the portrait that has given us an image for playwright Christopher Marlowe may be more important than either of these, as Marlowe ranks closer to Shakespeare in the history of English literature, in time, in style, and in reputation, than either Jonson or Fletcher. The son of a poor Canterbury shoemaker, his brief six-year moment as the protégé of aristocrats did little to contradict the evil reputation created by the government agents who destroyed him. The discovery of his portrait in 1952 by an undergraduate at his Cambridge college, Corpus Christi, who found it in a dumpster filled with trash, is little short of miraculous. The dates in the upper left corner support the identification, and our interpretation of his involvement with the Fisher’s Folly crew and their patrons, since the date on the painting, 1585 was his second year of unexplained absences from college. The splendid set of gold buttons that decorate his jacket would be hard to explain otherwise.

Despite the balloonlike nature of the immense jacket, perhaps a studio intern’s method of filling what space was left by the artist who painted his face, that face, the soulful eyes, most of all the energy and freedom expressed by the shock of upward sweeping hair, together with the quote from Ovid––“that which nourishes me destroys me”––may tell us more about Marlowe the poet-scholar than what scraps remain from his life. That it was paid for by the playwright himself and not a wealthy patron, is suggested by the fact that the hands were left out. Well-painted hands are difficult and time-consuming, so a portrait without them would have been less expensive.

Other literary figures also had their portraits painted. While those of Philip Sidney and John Harington, both courtiers, were related to their social status, poets from a lesser class like Michael Drayton and John Donne had theirs painted too, more than once in fact. We also have oil portraits of the actors who brought Shakespeare’s characters to life: Edward Alleyn, Richard Burbage, John Lowin, William Sly and Nathan Field. So why have we nothing for their author, the man who created the roles that brought them fame and fortune?

Engravings and woodcuts

The 16th century saw steel or copper engravings taking the place in printed publications of the cruder woodcuts of previous centuries. Richard Verstegan’s illustrations of the tortures and executions of English Catholics, published in Antwerp in the 1590s and conveyed into England by an underground Catholic network, are among the earliest. The following century saw the engraved portrait of the author take the place of the elaborate woodcut as frontispiece for their published works, as witness that of George Chapman, playwright, on his translation of Homer (1616); Samuel Daniel on his Civil Wars (1609); or John Florio on his Dictionary (1609).

The painstaking process of creating an engraving requires an original to work from, a portrait or drawing, some of which have survived. With the arrival of skilled artist engravers around the turn of the 18th century, we can be certain, for instance, that George Vertue’s “galleries” of engravings of famous individuals from an earlier time were derived from paintings, since by his time their subjects were long gone.

While we’re on the subject, it’s worth noting that two playwrights of the period, or writers who also wrote a play or two, are commemorated only by woodcut cartoons. This may make sense for Thomas Nashe, for as the satirical Piers Penniless or naughty Jack Wilton of the newborn popular press, Nashe would hardly rate anything more serious, but the absurd cartoon that is all we have for its founder, Robert Greene, is another matter. That England’s first great playwright Shakespeare, first great poet Spenser, and first great novelists Lyly and Nashe, have left no images, reinforces the likelihood that their works were created by artists who, repressed by the Reformation and its suspicion of Art as a tool of the Devil, could not allow themselves to be openly identified with works of the imagination.

Painted candidates

The lack of a believable portrait of the nation’s foremost literary artist has been keenly felt. Just as there are a good half dozen candidates for the authorship of Shakespeare’s works, there are upwards of a dozen portraits that have been promoted at one time or another as his image. In 2006 a rising British curator gathered six of these, together with a handful of portraits of other famous persons from the same period, for a travelling exhibit titled Searching for Shakespeare, which I had the good fortune to see at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven CT. Three of the six presented––the Soest, the Sanders, and the Flower––however long their moments in the sun, are no longer worth discussing. That leaves three: the Grafton, the Janssen, and the Chandos––plus the one that got left out.

The Grafton should be more important than ever, not because it’s a portrait of Shakespeare, but because it’s probably another portrait of Christopher Marlowe. (Isabel Gortázar, a Marlovian, has noted the same thing in a 2009 blog.)

Everything about it fits. The dates that remain in the corners of the painting: “Age 24” and “1588” certainly fit: Marlowe was born in 1564; in 1588 he was 24. In 1588, following his first great success with Tamburlaine, he was at the pinnacle of his career.

The trail of the portrait’s provenance leads to the Earls of Grafton, offspring and descendants of Barbara Villiers, mistress of Charles II during the Restoration of the Crown and Stage, who took also actors as her lovers during a period when Court society was in many ways indistinguishable from the upscale London theater audience. No longer identifiable (perhaps trimmed following Marlowe’s murder and the destruction of his reputation), it could have found its way with other theatrical flotsam to the King’s mistress, or later to her son, ending up in the remote village inn where it was discovered in 1907.

The Janssen too needs explaining. Long regarded as the true image of the Bard, it was knocked out of the running in 1947 when infra-red photography revealed that its bald head was due to the same overpainting found on other fakes. Over the years the addition of a bald head to a number of portraits of unknowns, obviously to make them conform in at least the most obvious way to the Droeshout, suggests the increasing intensity of the need to find a suitable image for the great playwright. In 1988 the Folger Shakespeare Library had the overpainting removed, revealing a man with a regular hairline (as in the Cobbe).

Certain features remain, however. Apart from minor details like the exact design on the fabric, the jacket on the Janssen matches almost exactly the form of the jacket on the Droeshout, while the strange collar on the Droeshout is an abstract version of its lace collar.

Several odd things about the Droeshout jacket and collar that questioners have suggested were meant to convey a subliminal message about the identity of the sitter, things like the flat nature of the front of the jacket that some see as two left sleeves, or the unnatural distance between the collar and the subject’s left shoulder so that the collar and head appear to be floating in space. Since these are also true of the Janssen, and were not the result of overpainting, we can forget about a subliminal message, at least not from these oddities, which doubtless have more to do with 17th-century studio practice than with any hidden message.

By now there should be no doubt that the Janssen, and the recently discovered Cobbe portrait, the original of which the Janssen was a copy, were portraits of Sir Thomas Overbury, secretary to the King’s favorite, Robert Carr Earl of Somerset, Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household from 1611 to 1615. Why have so many portraits of Overbury turned up? First, though forgotten today by all but historians, Overbury was a very important man in his day. Second, it was standard practise among courtiers to have their portrait painted as a gift for an important patron, from it commissioning copies to be made that could be distributed among persons of lesser importance. But why has it taken so long for the Janssen to be identified? Why wasn’t his name and his age painted in the corners as with other leading personages?

Vain of his own good looks and of his important position as secretary to the Lord Chamberlain, the official who had the King’s ear, Overbury must have had his portrait painted as a gift for some important patron, copies of which would then be distributed among those of lesser importance. In April 1613, having gotten himself involved in a nasty Court intrigue, the King had him thrown in the Tower for insubordination, where he died in September from––as it later turned out––poisoned tarts. His sordid murder and the notorious public scandal that followed would have bereft his portraits of their social value. Those that survived did so by having the standard identifiying marks located near the borders of a painting removed by trimming two or three inches from around its edges.

The Cobbe, clearly the original of which the Janssen and others were copies, turned up in 2006 when its owner saw the Janssen at the In Search of Shakespeare exhibit and recognized it as the twin of a painting he had known since childhood. As a descendant of Charles Cobbe, Archbishop of Dublin from 1743 to 1765, the portrait came to him after passing from Cobbe to its present owner via Cobbe’s mother, a descendent of Sir Thomas Chaloner (1561-1615), the son of Queen Elizabeth’s ambassador. Having been Robert Cecil’s envoy to Scotland during his secret negotiations with King James, Challoner Jr. had thenceforth lived for years in princely style as tutor and chamberlain to the royal heir, Henry, Prince of Wales, the most likely receiver of the original from one of his father’s leading courtiers.

The Cobbe, clearly the original of which the Janssen and others were copies, turned up in 2006 when its owner saw the Janssen at the In Search of Shakespeare exhibit and recognized it as the twin of a painting he had known since childhood. As a descendant of Charles Cobbe, Archbishop of Dublin from 1743 to 1765, the portrait came to him after passing from Cobbe to its present owner via Cobbe’s mother, a descendent of Sir Thomas Chaloner (1561-1615), the son of Queen Elizabeth’s ambassador. Having been Robert Cecil’s envoy to Scotland during his secret negotiations with King James, Challoner Jr. had thenceforth lived for years in princely style as tutor and chamberlain to the royal heir, Henry, Prince of Wales, the most likely receiver of the original from one of his father’s leading courtiers.

In these early years of his father’s reign, young Henry must have received a number of such portraits as gifts. With his unhappy death in November 1612 while still under Challoner’s care, his longtime tutor and, in effect, his surrogate father, Challoner may very well have inherited the still valuable painting. Then when Challoner too died three years later, murder and scandal having robbed the portrait of its social value, it passed, minus its embarrassing identification, to his son James Challoner, then from him to his daughter Veriana, and from her to her son Charles Cobbe, sometime Archbishop of Dublin. (This seems a much more likely provenance than the one offered on Wikipedia.)

In any case, it’s clear the Janssen is only one of several surviving copies made from the original. The Cobbe is a much better painting than the Janssen; the body is a normal size, the jacket looks like a real jacket––not like the Jack of Spades from the playing deck––and there’s no mysterious gulf dividing the head and collar from the shoulders.

Why the bald head?

One of the questions that has accompanied the question of the Droeshout’s authenticity from the start is: why the bald dome? How, since all these portraits of unknowns were modified by changing an ordinary hairline to that of an egg did this become its chief identifying characteristic? That question is answered by the provenance of the most important of the six portraits from the exhibit, and one of the two that remain as hallmarks of the truth about Shakespeare.

The Chandos

The Chandos is the portrait that, ever since the Janssen acquired its natural hairline in 1988, has been the favored image for representing Shakespeare on book jackets and the internet. Everything about the Chandos, its history as well as the image itself, suggests that it is, in fact, a genuine portrait of William of Stratford. Why then, since it’s been a candidate almost from the beginning, has it taken so long to be accepted? Could the issue be literary snobbery? Is it because the sitter’s ordinary looks and dull expression don’t suggest what we would expect a great writer to look like? After reading a good deal of the discussion surrounding the Chandos, that does seem to be the source of its centuries-old problem.

The Chandos got its name from the aristocrat who owned it for awhile in the 18th century, James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos. That it was painted from life early in the 17th century by the otherwise unknown John (perhaps Joseph) Taylor comes to us via a note from George Vertue, the 18th-century engraver, whose involvement in the chaos surrounding Shakespeare’s image is discussed in a following page. According to Vertue, the portrait passed from Taylor to William Davenant, the play-writing entrepreneur whose love for Shakespeare preserved his plays through the Interregnum. From Davenant it passed to Thomas Betterton, the actor who returned Shakespeare to the stage at the turn of the 18th century. From Betterton it passed to a series of collectors of Shakespeare memorabilia, including the dukes of Chandos, ending with the Earl of Ellesmere, who, in the 1850s, donated it to the recently instituted National Portrait Gallery in London. As its first acquisition, the Gallery labelled it NPG1, an honor it’s held ever since.

The Chandos the true image of William

That the Chandos is a genuine portrait of William of Stratford is reinforced by its likeness to the Droeshout. While the jacket and collar of the Droeshout reflect the Janssen, a number of art historians see its face as derived from the Chandos.

Although somewhat elongated, and with a higher (more noble?) forehead, the facial features of the Droeshout match in size, shape, placement (and utter lack of expression) those of the Chandos. Most notable is the general shape of its hair. What seems most likely is that the engraver, Martin Droeshout, was presented by the Earl of Pembroke and/or John Hemmings, patron and manager of the King’s Men, with both portraits, and asked to make a composite of the two. Both would certainly have been available to them, the one through Davenant, the other one of the copies of the original, the Cobbe, that had been floating around since the death of Overbury and the 1615 disgrace of his patron.

But why, if the Droeshout was a makeshift, did the engraver choose to give it the bald dome fringed by the roll of black hair that has become the basis for the public’s idea of Shakespeare’s face? With the Chandos as the source of the Droeshout image, that problem is solved. The Chandos has had its hard times, as its fragile backing attests, and although retouched, never so much as to erase its original appearance, nor was its bald head and black hair a later addition. So, as the First Folio was aimed to reflect, however obliquely, William of Stratford as the author via its mention of a “Stratford monument” and the “Swan of Avon,” so the engraved frontispiece would reflect at least this one characteristic to satisfy those who may have known William personally.

Of course this begs the question: “Why not just make an engraving of the Chandos? If William was the true author, and the painting was of William, why create this strange amalgam for the frontispiece of his collected works?” This of course is another one of those questions that, to keep one’s academic standing comfortably secure, must never be asked! Instead, Martin Droeshout must be incompetent; the Chandos must be of someone else; the face in the Cobbe is much better looking––anything but the truth, so help me Birthplace Trust!

And while the strange jacket and collar of the Droeshout can be explained by the Janssen, the heavy black lines that define the edges of the jaw and collar, lines of a sort that the engraver did not use anywhere else in the portrait, lines that questioners claim make the face look like a mask, cannot be explained by either portrait. Of course the composite was required because William was NOT the true author, and the face that slightly resembled his and no one else’s on the face of the earth, was indeed a mask, as Droeshout and his clients––the King’s Men and their patrons, the Pembrokes––felt must be communicated to another small but powerful interest group, those who knew the truth about the authorship because they knew, or their parents had known, the author himself.

“Palpable lies, damned lies, lies as big as one of the Guards’ chines of beef”

That Vertue named Davenant as the painting’s owner also points to William of Stratford, since Davenant, whose claim to be William’s illegitimate son has, like his father’s portrait, been treated with scorn by the Academy, and doubtless for the same reason, sheer snobbery. Dates, location and contemporary report all provide sufficient evidence that Davenant was telling the truth about his parentage, and none that he wasn’t. Davenant wasn’t lying about his true relationship to William of Stratford (he’s usually referred to as his godson), nor were those who later maintained it, among them near contemporary Oxford natives like John Aubrey and Anthony á Wood.

The lie is not that William Davenant was William of Stratford’s son––the lie is that William of Stratford was the author of the Shakespeare canon. One big lie will spawn scores, hundreds, in Shakespeare’s case, billions of others. Thus any discussion of efforts to provide the world with an acceptible portrait of the evasive genius must include the dozens of altered copies and obvious fakes. Inevitably, when either the Droeshout or the Chandos is the basis of the copy, there’s an obvious effort by the copier, more successful with some, less with others, to make him seem a little more intelligent, a little better looking. Fortunately, or unfortunately, depending on one’s point of view, the Chandos remains the unaffected transmitter of an important piece of the truth about Shakespeare: it tells us what his standin looked like.

The Ashbourne

Finally we come to the most important portrait of all, the one that got left out of the official travelling show, the one that, while it can now be seen in the Founders Room at the Folger Shakespeare Library, remains officially buried in their category of altered copies and fakes. This is the portrait known as the Ashbourne, after the town in Derbyshire where it was “discovered” in 1847 by one Dr. Marion Spielmann, the first to peg it as a possible portrait of Shakespeare. Despite the subject’s nobleman’s attire, his bald dome made him enough of a contender for the true image of Shakespeare that, after a meandering provenance from one purchaser to another, it ended up in 1931 at the Folger, taking much the same place there as did the Chandos at the British NPG, the Folger opening for the first time the following year. Little did they know at the time what a can of worms this particular acquisition would soon become.

Finally we come to the most important portrait of all, the one that got left out of the official travelling show, the one that, while it can now be seen in the Founders Room at the Folger Shakespeare Library, remains officially buried in their category of altered copies and fakes. This is the portrait known as the Ashbourne, after the town in Derbyshire where it was “discovered” in 1847 by one Dr. Marion Spielmann, the first to peg it as a possible portrait of Shakespeare. Despite the subject’s nobleman’s attire, his bald dome made him enough of a contender for the true image of Shakespeare that, after a meandering provenance from one purchaser to another, it ended up in 1931 at the Folger, taking much the same place there as did the Chandos at the British NPG, the Folger opening for the first time the following year. Little did they know at the time what a can of worms this particular acquisition would soon become.

In 1938, an experienced documentary filmmaker and sometime art historian, Charles Wisner Barrell, got permission from the Folger’s first and most prestigious director, Joseph Quincy Adams, to use Eastman Kodak’s recently developed infra-red photography to examine the Ashbourne, the Janssen, and a third bald contender, to see what if anything lay beneath their painted surfaces. As Barrell relates in an article published in Scientific American in January 1940, the infra-red photographs revealed overpainting on all three, all from “some remote period,”which, whatever other changes were included, was chiefly intended to turn the sitter’s original hairline into the bald head that, thanks to the Droeshout engraving, was the Bard’s most recognizable feature.

This would have been significant enough as the means for dismissing all three as genuine portraits of Shakespeare had not Barrell seen enough in the Ashbourne to switch his focus to its status as a portrait of the Earl of Oxford. For just as the Grafton looks like an older Marlowe, so the Ashbourne looks like an older Oxford than the one portrayed by the Welbeck, painted when he was twenty-five.

When Director Adams agreed to allow Barrell to make his photographs, was he aware that Barrell’s other great interest was the authorship question? By the late 1930s, efforts by Looney, B.M. Ward and others had succeeded in establishing Oxford as a leading contender for Shakespeare’s laurel crown. A confirmed Oxfordian, by the time Barrell got permission from the Folger he was already aware of the similarities between the Ashbourne and the Welbeck, the one portrait of Oxford that no one has ever questioned.

So Barrell’s purpose, perhaps kept to himself while taking pictures of the portraits, must have been less of the Ashbourne’s status as a source of the Droeshout than of its identity as a portrait of Oxford. It’s unlikely that anyone else would have seen, via the infra-red penetration of the painting’s surface, what Barrell recognized as the coat of arms of the Trentham family, into which Oxford was married in 1592.

Why did the Folger attack the Ashbourne?

Here’s where the story gets weird, for with the bald dome eliminated, there is no firm connection between the Ashbourne and Shakespeare. Objects like the skull, a symbol of philosophy, or the book which could have been about anything, were often found in other portraits of the time. As for the individual who, probably at some point in the early 18th century had noticed the portrait of an unknown but attractive subject from the Shakespeare period and had it retouched to look like what everyone thought Shakespeare should look like so he could make a profit by selling it, it’s unlikely that such a one could have had any notion that it was a painting of the Earl of Oxford or even if he did, that Oxford would someday be touted as the true author. For all Charles Barrell had actually proved was that the portrait was of Oxford––not that Oxford was Shakespeare.

Then why has the Folger engaged in a half century of the worst kind of dirty tricks to prove, not that the Ashbourne isn’t Shakespeare, but that it isn’t the Earl of Oxford? Why have they often made it difficult for the public to see it? Why have they come close to destroying it through their criminal negligence and the ruinous alterations ordered by past directors? Why have they gone to such extremes, first to prove that it isn’t Oxford, and then, when that failed, to find someone else they can pin it on, ending finally with Hugh Hammersley, a later mayor of London, an absurd identification, easily dismissed by anyone with two eyes and a smattering of history.

As authorship scholar Jeremy Crick notes in his 2007 article in the De Vere Society Newsletter, despite having retracted all claims that the Ashbourne portrays Shakespeare:

Yet still the Folger refuses to allow the ridiculous overpainted forehead on the painting to be removed––even though they know that the only proven protrait of Sir Hugh Hamersley, in the Haberdasher’s Hall in London, depicts him as an older man with a full head of hair. . . . Can there be any reason why the Folger would want to hold on to a painting of a minor Jacobean knight with no connection to literature?” (35)

Crick goes on to suggest that the Folger is hedging its bets in case Oxford triumphs and the Ashbourne turns out to be of immense value. Doubtless should that point ever be reached, the original hairline will be restored to its original state in record time, if by now such a restoration is even possible.

I’ve room here only for this brief outline of this distressing history, but those who are interested in the details will find links to the full story as revealed by authorship scholar Barbara Burris and a determined team of editors and supporters. Hopefully we haven’t yet heard the last of this facet of the search for Shakespeare.

Now for George Vertue and his images of Shakespeare.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/sir-thomas-overbury-15811613-228560

Where does this apparently larger image of Overbury fit in? Is the identification of Overbury as the sitter for the Cobbe in its resemblance to known images of Overbury? Are there any other hints that lead to Overbury?

Thanks for the link to the portrait in the Bodleian. But I’m not sure what you’re asking. Fit into what? Overbury apparently had a lot of portraits painted of himself, some cheaper copies of others. Quite a few engravings were made from some of these portraits as shown on the National Portrait Gallery website. The evidence of the resemblance of these other portraits and knockoffs is, or should be, obvious from the images above. If you want to know more about Overbury, I’ve put links above to my article on the link between Overbury and Webster’s The White Devil. Wikipedia has a bio on him.