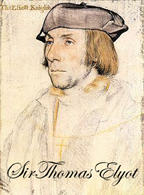

Edward de Vere was something of a pedagogical  experiment. In their Platonic desire for a Philosopher King, so eager were the humanistic reformers to educate the nobility, that, following Quintilian, Vives and Elyot, they sought to begin them as early as possible on Latin so that they would begin to absorb the wisdom of the ancients and early Church fathers while still young enough furnish their adult minds with the noblest and most idealistic thoughts. So while the Marian reign had its horrors, it did produce one benefit––to humanity that is––it sent the four-year-old heir to the Oxford earldom, in many ways the most important domain in England, to Sir Thomas Smith, the most highly qualified Reformation teacher in the nation. No doubt many were watching to see the outcome of this kind of training. This being the Reformation, you can believe that not all were pleased with the results.

experiment. In their Platonic desire for a Philosopher King, so eager were the humanistic reformers to educate the nobility, that, following Quintilian, Vives and Elyot, they sought to begin them as early as possible on Latin so that they would begin to absorb the wisdom of the ancients and early Church fathers while still young enough furnish their adult minds with the noblest and most idealistic thoughts. So while the Marian reign had its horrors, it did produce one benefit––to humanity that is––it sent the four-year-old heir to the Oxford earldom, in many ways the most important domain in England, to Sir Thomas Smith, the most highly qualified Reformation teacher in the nation. No doubt many were watching to see the outcome of this kind of training. This being the Reformation, you can believe that not all were pleased with the results.

Oxford himself must have experienced this interest as pressure, subtle perhaps, but still pressure, as seen, for instance, in the kind of criticisms and suggestions offered by Roger Ascham in his book, The Scholemaster, written for Cecil right at the time that he was first responsible for educating Oxford and Rutland. Oxford must have been aware from very early that all eyes were on him. “To whom much has been given, much is required.” What a disappointment it much have been to men like Cecil and Ascham and even to Smith when instead of another well-behaved, pious Sidney, who hadn’t begun his studies until the great age of seven, their prime experiment turned to poetry and plays, his vast education little more than grist for the mill of his comedies and love songs.

No doubt his elders gave him time. Poetry was a pastime of youth, something that, as with Thomas Sackville Lord Buckhurt would surely pass when the weight of mature responsibility awakened him to more important things. But as Oxford matured, his interest in literature only deepened. Scorned for his early efforts to join the international community of scholars, he channeled his talents into writing entertainments for the Court. This Cecil tolerated, probably because they pleased the Queen, perhaps also because he saw opportunities for help with the onerous business of creating the propaganda that was one of his most important weapons in the fight to destroy the political power of the Catholics.

As a peer, born to be a patron of the arts, Oxford had fallen into the trap that Elyot and other pedagogues had warned about in educating the nobility, he became an artist himself, and as an artist, as is always the case with a true artist, he held nothing higher than Art. This included rank and all the distinctions and constraints that it held dear. Clear to him from reading Plato was the distinction between the external world and the truth he felt within himself: “for I have that within that passeth show.” They wouldn’t give him the military command his patrimony required, nor the role in the government for which his training had prepared him, so he would fulfill the one thing he had, besides his rank, his inherited office of Lord Great Chamberlain.

The chamberlain of a Tudor household was a sort of glorified butler, one who ate at table with the family rather than with the staff. Often a member of the family from a lesser social level, or one whose family was tied in some way to the fortunes of the family he served, he was responsible for the smooth running of the household, including its removals to other locations and its entertainments at the three big turning points of the year, Christmas/Carneval, Easter/May Day, and Midsummer/St. John’s Day. At the Tudor Court, the Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household had the same functions, plus the honor and responsibility of serving as a leading member of the Privy Council. It was an appointed position, and although as with all such offices it was often given to the heir of the former Lord Chamberlain, that was only because having been raised at Court, he was often in the best position to fulfill the office.

England’s Lord Great Chamberlain was, and still is, a very different kind of office. Except for a brief time during the reign of Henry VIII, it’s one of a handful of inherited positions, a vestigial remain from the Middle Ages, when even then all it signified was that this fellow, his father before him, and his heirs after him, was the official best friend of the monarch. Since the earliest days of the Norman hegemony all that’s required of the LGC is that he appear dressed appropriately for processions in which his place comes after the Lord Privy Seal, and before the Lord High Constable, and that he act as personal attendant to the monarch at his or her coronation, something that generally occures no more than once or twice in a lifetime, or with a particularly long-lived monarch, not even that. From the very beginning this honorary office had belonged to members of the Vere family, as it still does today, having been shifted to descendants of Oxford’s sister Mary’s husband, Sir Peregrine Bertie (the Earls of Lindsay), when Oxford’s line died out with the death of the 20th Earl.

Looking around for something that could define his ambiguous role in his community, Oxford took advantage of this rather empty office, turning it into something genuine and powerful. It was probably as surprising to him as to anyone else when out of his genius and the great need of the English public for entertainment was born the Fourth Estate of modern government, what we call the media, which, in those days consisted of the London Stage and commercial Press.

There may be a kernal of truth to the rumor that Oxford ruined his patrimony out of revenge at Lord Burghley, though the proper wording would be out of the necessity to find something for himself in what he’d been left by his father. Awakening gradually to the horrible mess left by that foolish father; aware, probably from the start, that Burghley, his one and only financial advisor, was more concerned about his own family, their wealth and prestige, than he or they were about him; raised by the parsimonious Smith, whose ascetic diet and modest dress were the foundation of a lifestyle that, once the peacock period of Oxford’s twenties was over, required little more than a secretary, ink and paper; he used his wealth, whatever it was (he could never be sure) and his credit as a peer (for as long as it lasted), to praise his friends, wound his enemies and influence national policy by way of his favorite audience, the lawyers and parliamentarians of the West End. When his own credit and wealth ran out, he turned to the “angels” that every theatrical enterprise requires, chronologically: the Earl of Sussex, Sir Francis Walsingham, Lord Hunsdon, the Earl of Southampton and the third Earl of Pembroke, all of whom play an important role in their patronage of the great experiment we call Shakespeare.

Another insightful and stimulating essay.

Magnificent! Of course, this was an educational experiment gone profoundly right in many ways, as Emerson knew when he exclaimed, “What statesman has he not instructed in the ways of policy?” (I don’t have the exact quote, which includes instructing maidens in their virtue.) If only Elizabeth and her successors had understood the subtler messages interlaced or infused into the long drinks of heady propaganda: even Henry V is a model, in important ways, of how not to govern. Nothing is treated more urgently in Shakespeare than governance, whether it be the governing of a great state or simple self-governance, which intertwines in so many ways with the former. Smith instructed his pupil well.

Thanks Steve and Tom. Much appreciated.

” They wouldn’t give him the military command his patrimony required, nor the role in the government for which his training had prepared him, ….”

Why would they (that is, the Cecils) keep a command from Oxford? He apparently was physically able and skilled. I recall that he begged for service in the Netherlands. Did the Cecils want to prevent the possibility of his distinguishing himself as a way to retard his advancement? But Oxford was married to a Cecil.

Not sure how this point fits in with your thesis that here was an education gone bad as Elyot predicted.

Please keep the discussion going. Many thanks.

Francis Murphy

Of course I’m being ironic when I say that he was a failed experiment. The point is that what educationalists like Ascham and Smith were looking for with all that classical learning was a peer with wisdom, not a poet or a playwright, something that they had had enough of with aristocrats like the Earl of Surrey.

As for preventing him from having a military career, that was due largely to the fact that the administration, that is, Cecil plus the Queen, were never enthusiastic about getting involved in the wars on the Continent, so there wasn’t the opportunity that there had been for his ancestors, back when there was always a war going on somewhere where a young peer could cut his military teeth. The current war in the lowlands wasn’t much more than occupying a town or two, and hanging about to keep the Catholics from gaining more ground. If Oxford wanted so badly to be involved it may have been chiefly to get back to Europe and away from the English Court, where as he claimed, he was forced to play the “forehorse to a smock,” that is, play Hobby Horse (of the May Games) to the Queen (the smock).

And if Oxford was Shakespeare, as we believe, and so was providing the Court with outstanding entertainment, why would the Queen want to see him wasted on the field of battle? All her dealings with him suggest that her main interest was always to keep him close at hand and dependent on her for one thing or another so she could manipulate him into giving her what she wanted. What was that? Why, the kind of entertainment that made the English Court the envy of all the courts of Europe.

Many thanks for your prompt reply.

Are there contemporary reports amongst the diplomats (iin the 80s and 90s) of Elizebeth’s court being unrivaled for entertainment? And the quality of that entertainment being at all associated with anyone? Oxford?

For Francis, there are brief quotes or paraphrases, I seem to remember, of diplomats’ occasional remarks that the drama, even that given in the public theater, was one of the glories of the age. These can be found in Charlton Ogburn’s The Mysterious William Shakespeare, though they require some looking for. There are probably a fair number of such remarks in diplomatic correspondence of the time, though one would probably have to search a little outside the various Calendars of State Papers, since the documents therein summarized passed through the Cecils’ hands. Father Francis Edwards, a scholar of that period and one quite sympathetic to the authorship controversy, remarked on the curious lopsidedness of the records whenever someone rebellious against the Cecils was concerned.

Yes, thanks Tom. There’s no doubt but that the English actors were considered the best by the Europeans during the period in question. If someone would take the time to glean from the records the evidence for this they would be doing the authorship question a great favor. I just ran across more evidence recently in Ernesto Grillo’s Shakespeare and Italy, though the comment came from the latter half of the seventeenth century, by which time the battle for the London Stage had been over for some time. As for comments directly connecting Oxford with the Stage, no, for if we had, the argument over the authorship would have been over long since.

And, to be brief, it’s interesting that on one of the very few occasions when we know Elizabeth to have reacted to a play (know in a fairly trustworthy way), it’s precisely the time when Elizabeth got very angry with some student players and stormed out of the performance, as a Spanish diplomat witnessed. It would be just like the Cecils to leave this record untouched but excise all accounts written during the Queen’s life of how the mysterious “Shakespeare’s” plays “did so take Eliza and our James,” as Ben Jonson asserts, writing years later. I have no doubt that her war against the Puritans, however, was quite real, and that she valued her nobleman playwright.

Elizabeth was a Virgo, and having known many myself, I think I can say that, one thing that’s almost always true of Virgos is that they have a good and ready sense of humor. I have an imagined picture of the eleven-year-old meeting the Queen for the first time at his father’s entertainment where the play King Johan was performed, and that he was most impressed by her red-gold hair, still unwigged, and her laugh (though not at the play, which wasn’t at all funny).

Though not ugly, Elizabeth was no beauty, and no doubt she could look pretty severe, considering all she had to contend with, except when she laughed. I have a feeling that when he was first at Court his goal was always to make her laugh. Tarleton could do it with antics and repartee. Oxford sought to do it with witty dialogue, though I imagine his repartee was pretty choice as well. But of this of course there’s no proof.

Yes, and the traditions, like that one about her asking for a play showing Falstaff in love, or about the courtly wedding where A Midsummer Night’s Dream was performed, have to do with comedy, which, by the way, was said by Samuel Johnson to be Shakespeare’s natural metier: the tragedies, he had to work at a bit harder.

To be sure, Jacques Barzun says, somewhere in From Dawn to Decadence, that “comedy” was often simply a synonym for drama at this time in history, so we needn’t pin down Edward de Vere’s reported talents to the restricted field of laughter and amusement. The anonymous writer of the printed 1609 foreword to Troilus and Cressida praises “this author’s comedies…which serve as the most common commentaries on all the actions of our lives.” Note that “all.” (I’m quoting from memory.) And there is really very little to laugh at, except bitterly, in Troilus. The events hold us in appalled fascination at just how dismal human behavior is here.

With Oxford’s biography and the historical background in mind, the plays can be roughly placed in four categories. First are the comedies written originally for the Court during the 1570s. These include all the pastorals, As You Like It, All’s Well, Two Gents, plus the so-called “late plays,” Cymbeline, Winter’s Tale, Pericles, Two Noble Kinsmen, which are only late because they were revised by other writers, probably after Oxford’s death. Next are the history plays, most of them written for the Queen’s Men to perform on the road as a stimulation to the young men of the coastal towns whose response to a Spanish attack was of great concern to Walsingham. Written about the same time, after the fall from grace in 1581, for the lawyers and parliamentarians of the West End (not for the Court), were the first versions of serious plays like Hamlet, Julius Caesar, Coriolanus and Romeo and Juliet. Next come the “problem plays,” written in his maturity when he had lost his romantic outlook. These include Richard III, Troilus and Cressida, Antony and Cleopatra, Measure for Measure, and finally, King Lear. Some of these, like Lear, had an earlier incarnation in a different genre before the revision that changed their tone. A final period, probably the last four years of his life, saw the polishing of his favorites: As You Like It, Hamlet, The Tempest. Some of the plays were revised a number of times over the years.

One should read A.P. Rossiter’s fantastic essay, “Angel with Horns”: The Musicality of Richard III” to appreciate how deep Shakespeare’s genius went. It is written like a symphony with deep musical understanding in point counter point of “note” from the large (Acts) to the lines.

Amazing critique.

Dan Wright points out also in the “Henirad” that the structure moves from “Catholic-Cathedral” (Richard II” to Protestant free form “Henry V”.

Shakespeare had jazz feeling before jazz was invented as Hamlet has incredible improvisational feeling in the language.

A LOT of musical influence in this stuff.

Improvisation has always been a constant in music, originally the word jazz meant only that it had a syncopated rhythm. There are Bach’s variations. Liszt, like many of the great nineteenth century pianists, was all about improvisation. All writers “improvise,” unless you want to call the process of producing text “channeling.”

Someday when Oxford is accepted as Shakespeare, much will be made of the fact that he only began to study music in his teens, for Smith had no interest at all in music, claiming he couldn’t understand what others heard in it. And most of the poems we have that bear Oxford’s name or initials were actually song lyrics, so we can be fairly certain that he also composed their melodies. The madrigalist John Farmer claimed he was as good as any professional musician.

Merchant of Venice is suffused with music; it would make a great opera. Verdi loved Shakespeare: Falstaff, Otello.

The greater the poetry, the closer it comes to melody: Hopkins: “The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation.”

Truly we are in a “drab era” now with regard to poetry. But another Renaissance will come when once again words will be suffused with melody and rhythm as well as imagery and meaning.